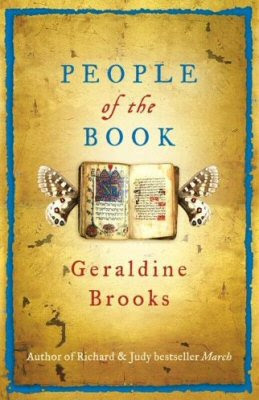

Books Geraldine Brooks's last book, March, was a Pulitzer prizewinner and found itself in Richard and Judy's Book Club reaching both ends of the critical spectrum. In that work, Brooks celebrated Louisa May Alcott's novel Little Women, a childhood favourite of hers, by presenting the parallel story of the March family's absent father fighting in the American Civil War. The historical evocation of literature continues in Brooks's new novel, People of the Book, which describes the investigations by Hannah, an Australian rare book expert into the Sarajevo Haggadah, a Jewish sacred text which has survived for just over five centuries through wars and inquisitions.

The structure of the book is somewhat similar to Vincent Ward's luminous film The Red Violin, in which the titular instrument's life from ancient creation to contemporary auction was described through an intricate flashback structure, with near short films presenting the various owners of the violin. As Hannah discovers items stuck between the leaves and in the binding of the book, the action changes to the period in history where the book enveloped them from a priest during the inquisition to a museum working in Bosnia during the second world war. Linking these stories is a sense of a work of art forever being saved for future generations even when its Jewish religious utility conflicts with the prevailing theology of the time.

At times, this is an extraordinarily detailed text, keeping the reader aware of the sounds, images and particularly smells in an environment. One of the best scenes in the book occurs when Hannah comes into contact with the Haggadah for the first time, as pages are given over to putting the reader in the position of this privileged expert forensically turning the pages making us understand what she's expecting and also surprises her; the sense of the scent and feel of the pages is so clear that to the extent that we could imagine the new book we're reading the description from has similar properties. The author is careful to modulate this however and it's frequently the case that when scenes are set against a modern backdrop, the dialogue is more fluid and expository.

The problem is that although the Haggadah is an intriguing object, the structure of the novel, which is essentially an anthology with Hannah's story, told in the first person, weaving in and out, leads to a certain lack of impetus which despite everything makes it quite an arduous read. There's a repetitiveness to the Australian's discover of a new property - an insect wing or a wine stain and then the appearance of a story which explains how it got there. The intent could have been to mirror these ancient manuscripts which would feature a range of stories and ideas, some which only tangentially tie together, and perhaps it does work on the level of a short story collection with a connecting tissue. But Hannah's character is so attractively drawn, and the novel so comfortable amidst her observations, that it's a pity Brooks couldn't have found a way to present the whole story of the people of the book in her words.

No comments:

Post a Comment