Art Watching as many television antiques programmes as I somehow do, I couldn’t fail to recognise Tim Wonnacott walking towards me at the Walker Art Gallery this morning. He was presumably visiting with a film crew for the next series of Bargain Hunt but was gone before I had a chance to ask him one of those questions I’ve often idled away at when I see otherwise professional dealers and auctioneers presenting these educational inserts for shows that would otherwise amount to just buying and selling. How do they switch it off or more precisely, can they visit art galleries and museums and enjoy the objects for the aesthetic qualities without attempting to size up their monetary value as well?

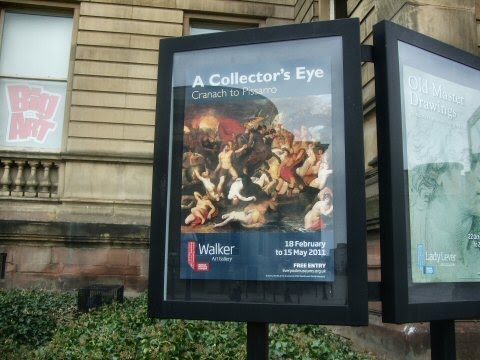

Coincidentally, the Walker’s latest exhibition, A Collector’s Eye: Cranach to Pissarro, also intertwines these twin values. This is a selection of pictures from the four hundred strong Schorr Collection, which has been assembled by collector David J Lewis over the past thirty-five years. It's the kind of private haul which in earlier times could have been amassed by some local businessman and, through loan, donation or bequest might have been the basis for many of the collections of the many regional museums and art galleries I’ve visited in the past few years. Lewis's taste, as the subtitle for the exhibition suggests, is for 15th-century devotional images and 19th-century French Impressionist landscapes.

As I think we discovered when I opened up my collection a couple of weeks ago, more than film and music, but not unlike food, most of us have very specific tastes when it comes to art and mine don’t quite match Lewis’s which meant the first half of the visit was a bit disappointing. Most of these large canvases are very skilfully painted and colourful but left me feeling curiously blank no matter the pain and suffering some of them depict (cf, Cranach's Lamentation over dead Christ). But wanting to draw something from the experience, knowing Wonnacott was talking enthusiatically to camera somewhere in the building and inspired by the Walker’s request for us to think about the kinds of paintings we’d like in our own collection I hatched a plan.

I decided to pretend that Lewis had put all of these paintings up for sale and that with the infinite pretend funds that were now making my pockets bulge I could take one of his paintings home with me. Now the question wasn’t “Do I like this?” it was “Would it fit on the wall of the huge invisible mansion I’ve just acquired?” After strolling about a bit more and stroking my imaginary moustache, I decided that actually my vast fortune was large enough that I could treat myself and that really I should have two paintings. So I lifted François Marius Granet’s Interior of the Capuchin Monastry, Rome and Louis-Auguste-Gustave Dore’s Scottish Landscape into my trolly and headed for the tills.

It’s the lighting which stands out in the Granet, the painter skilfully building the scene from autumnal yellows and browns, the shapes on the curved walls of the monastery and the cowls of the figures defined by greays and blacks not unlike the cinematographer Gordon Willis, who was nicknamed the prince of darkness for his similarly dark photography in The Godfather. There’s also a curious amount of action in what should be a relatively static scenes, the friars depicted in various states of prayer some more energetic than others. In the accompanying catalogue we also discover that the painting is more accessible than most since the artist painted many versions, often with slight variations – some even include nuns.

Dore’s landscape has some elements which can’t be replicated in photography. A massive panoramic image, depicting a solitary figure in a Scottish wilderness stretching on for miles the artist’s brushwork gives the rocks and trees realistic textures and shading that creates an impression that’s welcoming but tinged with foreboding. He visited the highlands in April 1873 and resolved that most of his work after that would be “reminiscent” of the place – which is why I was drawn to it. Unless I’ve misread the accompanying text, this isn’t from life, it’s from memory and it’s just the kind of fantasy location my little cottage would be in. Though obviously if I really was rich enough I’d gladly give up both images to go and live in that cottage instead.

So I metaphorically put the paintings back on the wall before the thought police came.

No comments:

Post a Comment